Men’s Rehabilitation Therapy Thesis

We’ve come into a dynamic and challenging era in the new age of Gender in the United States. As sexual equity has increased, creating more egalitarian opportunities for both men and women. The challenges of sexual fluidity, the marginalized intersex community and the cohesive definition of gender remain as frontiers to be mastered. This challenge is prevalent in our lives as it determines our proclivities, anxieties and coping mechanisms in our most basic Belonging Needs as outlined in Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs. As a man navigating gender equity and my role as well as future as a holder of the XY chromosome, I’d like to ensure I can understand how I fit and pass that on to my own offspring if I am ever so fortunate to bear any. As a rehabilitation counselor, privileged to be a sexually fluid, cisgender masculine identifying male, I’d like to expand my practice to specialize in men’s rehabilitation. I feel my Master of Science in Rehabilitation Counseling; my work experience in counseling; and my strong network into both the straight and LGBT male communities provide me a demographic from which I can both gather and provide transformative data. As well, I feel my Bachelor of Art in language; my art studio; and my professional experience in both fitness and modeling; can help me form effective experimental designs as well as therapies to assist men in navigating, mastering and finding satisfaction in both their male sexuality, orientation and gender identity. In a Ph. D program, I’d like to pursue the hypothesis:

Through art, drama and sex therapies focused on photography, modeling and role play, men can be cognitively, psychiatrically, physically and sexually rehabilitated in the effect of reducing homophobia, sexist anti-female bias, sexual dysfunctions, body dysmorphia and general antisocial personality disorder related behaviors. I’d like to pursue this using conventional, boudoir, physique and Avant Garde film and photography to produce “process film and images” in which the client (a male), counselor (myself) and the surrogate (art viewer) can use CBT, appreciative inquiry and motivational interviewing to achieve both internal and external results of self-improvement accordant to gender and sex egalitarian goals as depicted through the performance of visualizations.

To properly discuss male rehabilitation with the challenges of our new era of sex and gender freedom and transitions, we need to ask and define what the terms of the conversation mean. Many terms on the tables that have grown out of Feminist and LGBT discourse have been under attack and not objectively analyzed. And as a result, the core technology we use in this discussion to improve society—language—has become convoluted. Complicated questions have arisen like, “What’s the difference between unisex vs gender neutral?”; “Does toxic masculinity mean masculinity is toxic?”; “Isn’t feminism only for white women?”; “How is a masculinism movement not inherently misogynistic?” etc. Because of cultural and policy factors of the USA like abstinence only until marriage education (AOUM), inadequate sexuality education for students with disabilities, etc. education on the basic terms of sex and gender are too much of a dire risk for the public and professional world assume (Fine, 2006, p.307-308).

Because the conversation is so sophisticated, before we fully engage we all have to scale back our questions to more simple elementary basics that we thought we knew, but are actually more complex, like, What is sex? What is sexuality? What is gender? What is orientation? I’ll initially explore these terms and as the paper unfolds, I’ll explain and apply other terms as they arise in an analysis of my hypothesis.

What is Sex?

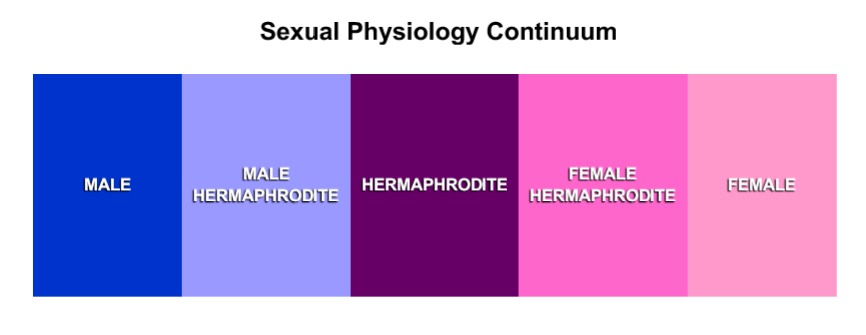

Sex is both noun and verb. While it can apply to action that incudes procreation, it also serves as mechanism of stress relief, social bonding, reconciliation, trust building, performance and even business. However, as a noun it classifies how we are born from our mothers and our genital descent. The sexual types are not just male or female, but usually termed intersex: hermaphrodite (herm), male hermaphrodite (merm) and female hermaphrodite (ferm). Intersex hermaphrodites usually have sexual organs and features solidly in the middle. Intersex male hermaphrodites present as male, but internally have female organs. And Intersex female hermaphrodites present as female although their internal equipment is male. In more medical language, the varieties of intersex are congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) and especially rare, 5-alpha-reductase deficiency (5ARD). However, when we look at forms, we are only offered “male” or “female” (our sex). There are never any squares with “male, merm, herm, ferm and female” nor forms with “XX, CAH, AIS, 5ARD, XY”. As a public, we are ill-informed and our understanding of the varieties in which we humans naturally (without human tinkering) occur is quite low and tend to be restricted to limited segments of the medical community.

So, when it comes to the public, the proliferation of both non-information and misinformation forces the public to confuse sex with gender and restricts our discourse on both gender and sexuality. Gender identity discussions become even more convoluted when “cisgender” discussions tend to be heteronormative and focus on male vs female, while discussing the intersex minority remains taboo if not marginalized. When people explore more common non-traditional sexuality and gender realities like transgenderism or transsexualism, the common focuses are male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM) dynamics. It is virtually never that you see male-to-intersex (MTI) or female-to-Intersex (FTI) procedures nor patients who seek it specifically as a goal. When people discuss cisgender privilege or how case documents should have “male”, “female”, “transgender”, it often is a faux pas of heteronormative privilege. In a culture of pathological binary thinking, the intersex-positive stance can revolutionize and reenergize discussions between the sexes and balance some of the arguments of the transgender/ transsexual movement. Transitioning sex to either male or female is a privilege for anyone of a cisgender birth, while born Intersexual individuals never had the opportunity to choose formal identifiers of “male”, “female” and especially their birthright term: “intersex”.

Sexual Physiology continuum

What is Gender?

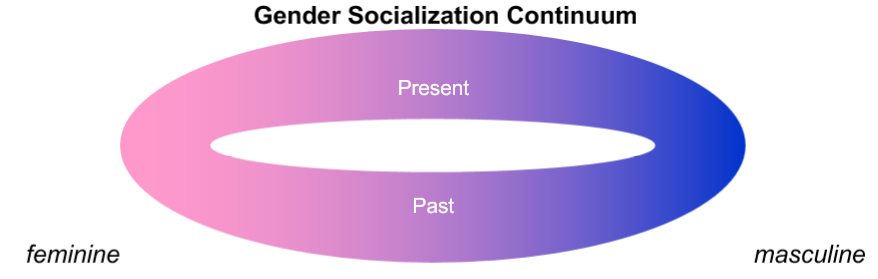

Oftentimes when discussing human sexuality and gender, controversy ensues because not are the two confused, but there is also a large degrees to which gender is non-biologically socially constructed and rooted in communication, art, language, etc. In order to succinctly understand it, the public must establish a valid definition of gender in order to meaningfully discuss it as well as govern it. Often in society we carry the misconception of gender based in Sex Role Theory (SRT) which “fosters the notion of a singular female or male personality, a notion that has been effectively disputed, and obscures the various forms of femininity and masculinity that women and men can and do demonstrate” (Courtenay, 2000, p. 1387). This essentially points out that the idea of gender is one we continue to conflate and confuse with sex. While SRT tries to convince us that sex and gender are not only binary, but they are synonymous as well. However, the research and science support that both physical sex as well as social gender are neither binary, yet both varied. However, Courtenay goes on to elaborate on a few ways gender works:

- From a constructionist perspective, women and men think and act in the ways that they do not because of their role identities or psychological traits, but because of concepts about femininity and masculinity that they adopt from their culture. (Pleck et al., 1994a).

- Gender is not two static categories, but rather “a set of socially constructed relationships which are produced and reproduced through people’s actions” (Gerson and Peiss, 1985, p. 327);

- It is constructed by dynamic, dialectic relationships (Connell, 1995). Gender is “something that one does, and does recurrently, in interaction with others” (West and Zimmerman, 1987, p. 140; italics theirs);

- It is achieved or demonstrated and is better understood as a verb than as a noun (Kaschak, 1992; Bohan, 1993; Crawford, 1995).

- Most importantly, gender does not reside in the person, but rather in social transactions deemed as gendered (Bohan, 1993; Crawford, 1995).

- Gender is viewed as a dynamic, social structure.

- Gender is constructed from cultural and subjective meanings that constantly shift and vary, depending on the time and place (Kimmel, 1995).

For a physiological comprehensive answer definitive to both gender and sex, Trogrimson and Minson state:

“Accordingly, it is imperative that scientists and editors come to a consensus on these terms to alleviate any confusion in their usage. These words have specifically different etymologies and meanings. In the most basic sense, sex is biologically determined and gender is culturally determined. The noun sex includes the structural, functional, and behavioral characteristics of living things determined by sex chromosomes. Sex (noun) is derived from the Latin word “sexus,” meaning either of two divisions of organic nature distinguished as male or female, respectively (8). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, sex (noun) has a definition as “the sum of those differences in the structure and function of the reproductive organs on the ground of which beings are distinguished as male and female, and of the other physiological differences consequent on these; the class of phenomena with which these differences are concerned” (8). Gender can be thought of as the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex. Gender (noun) is derived from the Latin word “genus” referring to kind or race (8). Gender (noun) is defined as “a kind, sort, or class referring to the common sort of people” (8). It is through an understanding of these principal definitions that scientists can apply these terms in a specific manner to sex-based research.” (Trogrimson and Minson, 2005, p. 785).

Gender Socialization continuum

The reason for this clarification is rooted in a couple of deficiencies of the medical science community that were made apparent during the 1985 US Task Force on Women’s health that prompted the rise of sex-based research. The task force found:

- Until the 1990s many American trained physiologists had been unclear on the difference between sex and gender although information proliferates other fields: “Increasingly, researchers are becoming aware of the appropriate use of the terms sex vs. gender. Still, some scientists are vaguely aware that a distinction exists between these terms or that this difference is an important one.” (Trogrimson and Minson, 2005, p. 785).

- And the technical specifications of the medical establishment were configured to male health (the medical norm group was that of a 70kg male) at the expense of female health: “The prominence of research investigations using the established “norm” of a 70-kg man shaped an understanding of human biology that lacked information in regard to female specific biology, anatomy, pathology, and treatments for disease. As a result, in 1985 US federal government declared that women’s health care sciences were insufficient and prompted legal action towards “sex-based research” that has fundamentally changed modern American medical sciences.

What is Sexual Orientation and Fluidity?

Breaking down human behaviors into basic points of solid, semi-solid and fluid—like the physics of hydrogen bodies sex and gender vary across geography and time. All human behavior should be similarly varied and accordingly proper analysis between the sexes should show a relative fairness in distribution of both heterosexual and homosexual behaviors.

Evidence of human sexual and diversity exist it the “two-spirit” and “berdache” phenomena throughout indigenous North and South America; In both Europe and America, there not only is a controversial and vibrant LGBTQ culture, economy and politic, it stems out of ancient traditions as old as both Roman and Greek empires—traditions that even the modern churches still wrestle with today; Africa and the Middle East both exhibit historically demonstrate an organically occurring participation in gender and sex fluidity despite the prevalence of inhumane and prescriptive religious dogma. Although modernly prohibited, phenomena such as eunuchs have proliferated male dominated Middle Eastern cultures. And additionally, many indigenous African cultures featured matriarchal female leadership traditions’; And again in Central and Eastern Asia, sexuality although has often been formally cisgender and heterosexual, infomral agreements and market culture have lent themselves to vibrant and distinctive alternative sex cultures.

Despite the timeless information on the flexibility and relativity of human sexuality, modern sex culture tends to stay polarized in a variety of ways like sexual activity versus sexual inactivity; heterosexuality versus homosexuality; sex for profit versus sex for free; sex for meaning versus sex for pleasure. To answer what is sexual orientation and fluidity, we also have to ask what are all the social, psychological and physiological functions of sex as well. Fahs touches upon a variety of interesting qualities that include “performative sexuality” (Fahs, p. 433, 2009). In the context of bisexuality and its common erasure or marginalization as temporary, choice, or farce (Fahs, p.434). Which goes to say that “performative sexuality” can be demonstrated hypocritically to one’s identifying sexuality; it is mechanically achievable despite notions of attractiveness or preference; it is aesthetic; it is flexible. The definition is derived from Fahs, “performative bisexuality”:

“where women often deny the significance of same-sex encounters even while engaging in them, thus further challenging the meaning of bisexuality as a permanent or meaningful identity”.

In the context of women’s sexuality more readily adapts to cultural scripts and expectations and therefore indicates a plastic nature to human sexuality (Fahst, p.435). Feminist theory highlights the plasticity of human sexuality in the female context, but this also can be generalized to male as well. Although literature tends to focus solely on what sex is most inclined to “erotic plasticity” (Baumeister, p.133, 2004), the real indicators for objectively recognizing and universalizing the phenomena is to look at the conditions that facilitate orientation in not just women, but also men—which this paper aims to do.

From a sociological viewpoint, comparative studies of men’s vs women’s erotic plasticity in a time period and cultural context in which dominate the sociopolitical landscape seems Western-centric and predictably skewed. And as modernization touches upon the world, it is important that we consider factors like time, geography, politics, etc. to make any accurate statement regarding orientation as it relates to gender and behavior between the sexes. Then we also have to acknowledge our contemporary factors as they influence the sexual ideas and habits we classify as “normal” in order to maintain a scientifically informed idea of average orientation and sexual fluidity.

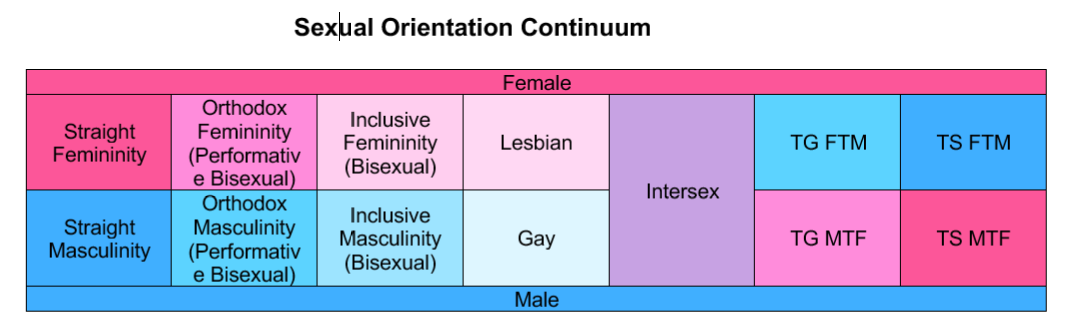

From survey analysis of scholarly articles, women tend to be a major focus for orientation studies. Many articles are written under the presumption of ambiguous orientation for women, often describing their behaviors with terms such as ‘bisexual”, “sexual fluidity”, “sexual plasticity” or “erotic plasticity”. However, a quick glance of male focused studies—which tend to be segregated by either gay/ homosexual or straight—use the term “situational homosexuality” (Anderson, p. 112, 2008). Other terms that arise are “heteroasculinity”, “heteromasculine currency”, “good cause (for homosexual behavior)”, “heterosexual social identity threat”, “masculine capital”, “inclusive masculinity”, “feminine coding”, “sexual object appropriation (gay or female for power)”, “queer sexism” (Anderson, p. 110-112, 2008). In this discussion of “orthodox masculinity” versus “inclusive masculinity”, we get to see a framework on how bisexuality and fluidity become negotiated and labeled—no remain unlabeled altogether.

Orthodox Masculinity

Men are sexually fluid however depending on their gender take different approaches. Orthodox masculine men will “slightly alter a traditional, sexist version of masculinity by inviting gay men to participate in their anti-feminine attitudes (Anderson, p. 111, 2008). They condone homosexual and bisexual activity and even group sex, but not feminine expression (queer sexism) nor activity that includes gay identified men, and must be without the admission of same-sex desire.

Inclusive Masculinity

On the inverse is inclusive masculinity which makes masculinity available to gay men and femininity available to straight men. What’s most interesting is how Anderson describes the not only non-toxic, but socially reparative effects of inclusive masculinity:

“These informants even celebrate the expression of femininity among men and stigmatize men who act in orthodox masculine ways. To these men, Carson is a source of pride. Thus, men exhibiting inclusive masculinity not only separate the hegemonic powers of sexuality and masculinity from heteromasculinity, but they contest the privileging of orthodox masculinity over inclusive masculinity and (to a lesser extent) the privileging of men over women” (.p111, 2008).

Inclusive masculinity men don’t require a heterosexual, conquest “good cause” motivation. Inclusively masculine orientation also sees various forms of homosexual contact (kissing, oral, masturbation) as compatible with heterosexual orientation.

From Anderson’s study, the frequency of same-sex behavior between both the orthodox masculine and inclusive masculine qualitative test groups was equal (p. 111). This reinforces that bisexuality is not unique strictly to the female population. In addition it means that men do navigate between the two polarities of orientation—homo and hetero. However the incidence of sexuality seems more frequent, varied and competitive than the women. This is suggested in the data that highlights the group sexual behaviors and the transactional logic of Orthodox masculine sexuality orientation (which is masculine currency weighed) as well as with Inclusive masculine sexual orientation (which is non-judgmental).

The Multitude of Masculinities

Finally gaining an understanding of male sexual fluidity fills in some of the gaps especially due to the sexist bias in medicine and sexology evident in the 1985 Women’s Healthy Taskforce and the lack of research on male, non-gay bisexuality. Away from the traditionally assumed categories of men—straight or gay (opposed to women’s straight, bisexual, lesbian), it can be now seen that masculinity for men is even more varied: straight, bisexual (orthodox masculine, inclusive masculine) and gay. Thanks to this deeper understanding of male sexual orientation, it can also be applied toward female studies as well, demonstrated in the following figure.

The figure displays an orientation continuum that accounts for gender currency as well as physical sexuality.

What is Men’s Rehabilitation Therapy?

After the analysis of Anderson regarding the structure of male sexuality ad gender, the heavy lifting of the said concepts constitutes the reconstruction of varied, socially sustainable masculinities. Anderson identifies Orthodox Masculinity that frames the male definition of sexual experience: transactional, competitive, prescriptive, hegemonic and misogynistic. The definition clearly facilitates an ambivalent male gender and sexuality, free of social accountability nor repercussions. It serves for exclusion and “them vs us” psychology. However, Inclusive Masculinity achieves the opposite as it is often unlabeled, gender-fluid and sex-fluid. But first we have to look and ask, just how is Orthodox Masculinity problematic and in need of reform? What are the major social challenges that we have now and how might the exacerbated or alleviated depending on the approach of masculinity?

In exploring gender and all its complexity, my personal interest and motivation is in male gender expression, sexuality and masculinity of men. Feminist Theory has posited a plethora of positive points and contributions towards the empowerment of women as well as the recruitment of feminism allies. It has also spurned motivation throughout LGBTQIA communities. However, as the knowledge unlocked from feminism has bettered society, it has also reverberated into producing negative effects: polarization of WASP men as well as paternalistic, female-negative men; the lack of minority men in nurturing positions; homophobia and marginalization of the sexuality of feminist male allies; male chauvinist MTF transgenderism; retaliatory insensitivity toward male children; and many other, seen but not heard social problems.

But through the conclusions of feminist theory—that gender is performed—I feel I can help the male world through the art therapy of modeling, performance and a safe space for the exhibition and artistic appreciation and eventually holistic rehabilitation of masculinity. Men’s Rehabilitation Therapy (MRT) takes on a restorative approach to negotiating masculinity and explores these areas which will be detailed later:

- The Performance of Gender and Drama Therapy for Rehabilitation

- Performance Catharsis and Body Dysmorphic Disorder

- Differentiating between Fitness and Bigorexia

- Gender Dysphoria versus Sex Dysmorphia

References

Fine, M., & McClelland, S. (2006). Sexuality education and desire: Still missing after all these years. Harvard Educational Review, 76(3), 297-338.

Torgrimson, B. N., & Minson, C. T. (2005). Sex and gender: what is the difference? Journal of Applied Physiology 2005 99:3, 785-787.

Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social science & medicine, 50(10), 1385-1401.

Nancy Krieger; Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections—and why does it matter?, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 32, Issue 4, 1 August 2003, Pages 652–657, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg156

Ernst, M. M., Liao, L. M., Baratz, A. B., & Sandberg, D. E. (2018). Disorders of Sex Development/Intersex: Gaps in Psychosocial Care for Children. Pediatrics, e20174045.

Griffiths, D. A. (2018). Shifting syndromes: Sex chromosome variations and intersex classifications. Social studies of science, 48(1), 125-148.